Hilário de Sousa

Study notes

These are linguistic notes for myself: they are not fully referenced, and there are not many examples. If they help you, great. n.b.: I cannot guarentee the accuracy of these notes.

Jump to:

Abkhaz

I had a quick look at:

- Hewitt, George. 2010. Abkhaz: a comprehensive self-tutor (LINCOM Student Grammars 03). Muenchen: Lincom Europa.

- Chirikba, Viacheslav A. 2003. Abkhaz (Languages of the world/Materials 119). Muenchen: Lincom Europa.

Alphabet/a little bit of phonology

Here are the Abkhaz alphabet organised phonologicaly. The inventory is that of the standard Abzhywa dialect (other dialects have more consonants). These are the consonants:

| П п | Т т | Тә тә | К к | Кь кь | Кә кә | Ҟ ҟ | Ҟь ҟь | Ҟә ҟә | |||||||

| /pʼ/ | /tʼ/ | /tʷʼ/ [t͡pʼ] | /kʼ/ | /kʲʼ/ | /kʷʼ/ [kʷʼ] | /qʼ/ | /qʲʼ/ | /qʷʼ/ [qʷʼ] | |||||||

| Ҧ ҧ Ԥ ԥ | Ҭ ҭ | Ҭә ҭә | Қ қ | Қь қь | Қә қә | ||||||||||

| /pʰ/ | /tʰ/ | /tʷʰ/ [t͡pʰ] | /kʰ/ | /kʲʰ/ | /kʷʰ/ [kʷʰ] | ||||||||||

| Б б | Д д | Дә дә | Г г | Гь гь | Гә гә | ||||||||||

| /b/ | /d/ | /dʷ/ [d͡b] | /ɡ/ | /ɡʲ/ | /ɡʷ/ [ɡʷ] | ||||||||||

| М м | Н н | ||||||||||||||

| /m/ | /n/ | ||||||||||||||

| Ф ф | С с | Ш ш | Шь шь | Шә шә | Х х | Хь хь | Хә хә | Ҳ ҳ | Ҳә ҳә | ||||||

| /f/ | /s/ | /ʂ/ | /ʂʲ/ [ʃ] | /ʂʷ/ [ʃᶣ] | /χ/ | /χʲ/ | /χʷ/ [χʷ] | /ħ/ | /ħʷ/ [ħᶣ] | ||||||

| В в | З з | Ж ж | Жь жь | Жә жә | Ҕ ҕ Ӷ ӷ | Ҕь ҕь Ӷь ӷь | Ҕә ҕә Ӷә ӷә | ||||||||

| /v/ | /z/ | /ʐ/ | /ʐʲ/ [ʒ] | /ʐʷ/ [ʒᶣ] | /ʁ/ | /ʁʲ/ | /ʁʷ/ [ʁʷ] | ||||||||

| Ҵ ҵ | Ҵә ҵә | Ҿ ҿ | Ҷ ҷ | ||||||||||||

| /tsʼ/ | /tsʷʼ/ [tɕᶠʼ] | /tʂʼ/ | /tʂʲʼ/ [tʃʼ] | ||||||||||||

| Ц ц | Цә цә | Ҽ ҽ | Ч ч | ||||||||||||

| /tsʰ/ | /tsʷʰ/ [tɕᶠʰ] | /tʂʰ/ | /tʂʲʰ/ [tʃʰ] | ||||||||||||

| Ӡ ӡ | Ӡә ӡә | Џ џ | Џь џь | ||||||||||||

| /dz/ | /dzʷ/ [dʑᵛ] | /dʐ/ | /dʐʲ/ [dʒ] | ||||||||||||

| Р р | И и | Ҩ ҩ | У у | ||||||||||||

| /r/ | /j, jə, əj/ | /jʷ/ [ɥ~ɥˤ] | /w, wə, əw/ | ||||||||||||

| Л л | |||||||||||||||

| /l/ |

For the letter pairs <Ҧ Ԥ> /pʰ/ and <Ҕ Ӷ> /ʁ/, The ones with descenders <Ԥ Ӷ> are the modern standards, but the ones with hooks <Ҧ Ҕ> are still widely used. The ones with descenders <Ԥ Ӷ> are encoded in unicode since version 5.2 (i.e. later than the ones with hooks), and might not render correctly in some devices. (<Ꚋ Ӄ> also existed in earlier Cyrillic orthography of Abkhaz, for mordern <Ҭ Қ>.) There is also a (marginal) phoneme /ʔ/, but I don't know whether it is written or not.

There are two vowel phonemes: /ə/ /a/. There is also a long /aa/, which came from an earlier */ʕa/ or */aʕ/. There are the vowel symbols <Ы ы> for /ə/ and <А а> for /a/, and also <И и У у Е е О о> for other realisations of the vowel phonemes:

- <И и> [i] is /ə/ in /jə/, /əj/, or /Cʲə/

- <У у> [u] is /ə/ in /wə/, /əw/, or /Cʷə/

- <Е е> [e] is /a/ in /ja/, /aj/, /jʷa/, /ajʷ/, or /Cʲa/

- <О о> [o] is the realisation of the sequences /aw/, /wa/, and /awa/; or /a/ in /Cʷa/

(In reality, things with the vowels are more complicated that this; let me read more about it / listen more first.) Stress is contrastive, but not indicated in the script.

Burmese

This section is primarily about the most common reditions of rimes in Burmese script, and their pronunciation in modern standard Burmese. (Please contact me if you see errors; I am still learning.) I am presenting them in two different ways that I find useful: arrangement based on dictionary order, and arrangement based on their phonology in spoken language. Unicode Burmese font is used here; the most commonly used font in Myanmar, Zawgyi, is encoded differently to Unicode. (On my computer at least,) Firefox renders Burmese script more accurantely than Chrome, so you might want to compare the rendition of Burmese script in different browsers.

Burmese script is follwed by MLC transcription, in italics. The MLC transcription is a transliteration of the written script; like many Brahmic scripts in Southeast Asia, there is considerable distance between the written script and the modern day pronunciation. You might want to have a look at, e.g., the Wikipedia pages on Burmese phonology and Burmese script.

Rimes in dictionary order

I read about the collation of Burmese script here:

Burmese script is a Brahmic script. Within each orthographic syllable, five types of script elements can be distinguished for the purpose of collation. These script elements largely correlate with the components in a phonological syllable. The collation hierarchy of the script elements is as follows:

- Onset

- Onset diacritic (approximant(s) in a cluster and/or the voiceless symbol)

- Coda

- Vowel

- Tone

- Vowel

- Coda

- Onset diacritic (approximant(s) in a cluster and/or the voiceless symbol)

For instance, in ကြောင့် kraung. 'because of', က k is the onset, ြ -r- is the onset diacritic, င် -ng is the coda, ော au is the vowel, and ့ . is the tone.

Onset

Basicaly follows the Brahmic script order. See the table here. In the table, read from left to right, and then top to bottom row by row. For the two varients of ny, ဉ precedes ည. Ignore the 'independent vowels' symbols for now.

Onset diacritic

The order is:

- no diacritic

- ျ _y

- ြ _r

- ွ _w

- ှ h_

- ျွ _yw

- ြွ _rw

- ျှ h_y

- ြှ h_r

- ွှ h_w

- ျွှ h_yw

- ြွှ h_rw

Coda

Basically any consonant symbol can be used to symbolise a coda by adding the ် a.sat diacritic to signify that it has no phonological vowel. For instance, က is ka., while က် is -k. They have the same order as the onset consonant symbols. Another way to symbolise a coda is using stacked consonant symbols: the normal consonant symbol is the coda, and the consonant symbol placed underneath is the onset of the following syllable. For instance, in မန္တလေး manta.lei: 'Mandaley' (the second city of Burma), န္တ n and t are stacked together; န n is the coda, and the တ t underneath it is the onset of the following syllable (in this case, /t/ becomes voiced /d/). The stacked consonants are collated in the same way as a normal consonant symbols.

Vowel

Some of the orthographic vowel symbols convey information more than just the phonological vowel. For their phonological values, see the rime table below. The following is the collation order of the orthographic vowel symbols; the vowel symbols are here placed around the zero onset symbol အ. The vowel symbol for a has two forms: the long form ါ and the short form ာ. The short form ာ is the default form; the long form ါ is used after ခ hk, ဂ g, ဒ d, ပ p, and ဝ w, to avoid them looking like other consonant symbols if they are followed by the short form ာ. The long form ါ is here accompanied by the onset ဝ w instead of the zero onset symbol အ. The vowel transcription is that of the orthographic vowel when it is not followed by a coda symbol.

- no vowel symbol (see their phonological values in the rime tables below)

- ဝါ / အာ a ( ါ / ာ cannot be followed by a coda symbol)

- အိ i.

- အီ i ( ီ cannot be followed by a coda symbol)

- အု u.

- အူ u ( ူ cannot be followed by a coda symbol)

- အေ e ( ေ is followed by a coda symbol only in loanwords)

- အဲ ai:

- ဝေါ / အော au: (The same rules for the long form ါ applies)

- ဝေါ် / အော် au (The above plus ် a.sat; this rime is in low tone)

- အံ (If there is no vowel symbol, ံ am is placed here. If there is a vowel symbol ိ i or ု u, then ိံ im or ုံ um are collated together with ိမ် im or ှမ် um, respectively)

- အို ui

Tone

The collation order is as follows:

- No tone mark (can be any tone, but often low tone. Low tone is 'no dot' in transcription)

- ့ creaky tone (creaky tone is 'one dot' . in transcription)

- း high tone (high tone is 'two dots'/colon : in transctiption)

- ့း marks genitive in some situations

Rime table in dictionary order

The following table presents the commonly encountered rimes in Burmese script. In each section the rimes of one or a pair of related vowel symbols are displayed. In the first one or two rows are rimes with no tone symbols, the following row are rimes with a ့ tone symbol, and the following row are rimes with a း tone symbol. (အော် (ဪ) au is put in its own row.) Each column are rimes with different coda symbols, starting with the first column with no coda symbol. For dictionary collation order, you need to read from top to bottom, and then from left to right column by column, because the coda symbol has higher priority than the vowel symbol in collation. The zero/ʔ onset symbol အ is used for the onset. Burmese script is followed by transcription in the same cell, and then its phonological form in the cell below. See also the notes following the table. (An online spreadsheet of this is also available here.)

| အ a. | အက် ak | အစ် ac | အတ် at | အပ် ap | ||||||

| [ʔa̰] | [ʔɛʔ] | [ʔɪʔ] | [ʔaʔ] | [ʔaʔ] | ||||||

| အာ a | အင် ang | အဉ် any | အည် any | အန် an | အမ် / *အံ am | အယ် ai | ||||

| [ʔà] | [ʔɪ̀N] | [ʔɪ̀N] | [ʔɛ̀] / [ʔì] / [ʔè] | [ʔàN] | [ʔàN] | [ʔɛ̀] | ||||

| အင့် ang. | အဉ့် any. | အည့် any. | အန့် an. | အမ့် / *အံ့ am. | ||||||

| [ʔɪ̰N] | [ʔɪ̰N] | [ʔɛ̰] / [ʔḭ] / [ʔḛ] | [ʔa̰N] | [ʔa̰N] | ||||||

| အား a: | အင်း ang: | အဉ်း any: | အည်း any: | အန်း an: | အမ်း / *အံး am: | |||||

| [ʔá] | [ʔɪ́N] | [ʔɪ́N] | [ʔɛ́] / [ʔí] / [ʔé] | [ʔáN] | [ʔáN] | |||||

| အိ (ဣ) i. | အိတ် it | အိပ် ip | ||||||||

| [ʔḭ] | [ʔeɪʔ] | [ʔeɪʔ] | ||||||||

| အီ (ဤ) i | အိန် in | အိမ် / အိံ im | ||||||||

| [ʔì] | [ʔèɪN] | [ʔèɪN] | ||||||||

| အိန့် in. | အိမ့် / အိံ့ im. | |||||||||

| [ʔḛɪN] | [ʔḛɪN] | |||||||||

| အီး i: | အိန်း in: | အိမ်း / အိံး im: | ||||||||

| [ʔí] | [ʔéɪN] | [ʔéɪN] | ||||||||

| အု (ဥ) u. | အုတ် ut | အုပ် up | ||||||||

| [ʔṵ] | [ʔoʊʔ] | [ʔoʊʔ] | ||||||||

| အူ (ဦ) u | အုန် un | အုမ် / အုံ um | ||||||||

| [ʔù] | [ʔòʊN] | [ʔòʊN] | ||||||||

| အုန့် un. | အုမ့် / အုံ့ um. | |||||||||

| [ʔo̰ʊN] | [ʔo̰ʊN] | |||||||||

| အူး (ဦး) u: | အုန်း un: | အုမ်း / အုံး um: | ||||||||

| [ʔú] | [ʔóʊN] | [ʔóʊN] | ||||||||

| အေ (ဧ) e | ||||||||||

| [ʔè] | ||||||||||

| အေ့ e. | ||||||||||

| [ʔḛ] | ||||||||||

| အေး (ဧး) e: | ||||||||||

| [ʔé] | ||||||||||

| အဲ ai: | ||||||||||

| [ʔɛ́] | ||||||||||

| အဲ့ ai. | ||||||||||

| [ʔɛ̰] | ||||||||||

| အော (ဩ) au: | အောက် auk | အောင် aung | ||||||||

| [ʔɔ́] | [ʔaʊʔ] | [ʔàʊN] | ||||||||

| အော့ au. | အောင့် aung. | |||||||||

| [ʔɔ̰] | [ʔa̰ʊN] | |||||||||

| အောင်း aung: | ||||||||||

| [ʔáʊN] | ||||||||||

| အော် (ဪ) au | ||||||||||

| [ʔɔ̀] | ||||||||||

| * | ||||||||||

| အို ui | အိုက် uik | အိုင် uing | ||||||||

| [ʔò] | [ʔaɪʔ] | [ʔàɪN] | ||||||||

| အို့ ui. | အိုင့် uing. | |||||||||

| [ʔo̰] | [ʔa̰ɪN] | |||||||||

| အိုး ui: | အိုင်း uing: | |||||||||

| [ʔó] | [ʔáɪN] | |||||||||

Some notes:

- Syllables can be reduced (minor syllable), if it is a non-final syllble in a word, or certain grammatical suffixes (enclitic?). When a syllable is reduced, the phonological tone and coda are stripped away, some (?) secondary articulatory feature of the onset is stripped away, and the vowel is reduced to a schwa [ǝ]. For instance, 'one' is တစ် tac [tɪʔ], 'two' is နှစ် hnac [n̥ɪʔ]. But when forming 'ten' and 'twenty', တစ် [tɪʔ] and နှစ် [n̥ɪʔ] are reduced to [tǝ] and [n̥ǝ] respectively: တစ်ဆယ် tac hsai [təsʰɛ̀] 'ten', နှစ်ဆယ် hnac hsai [n̥əsʰɛ̀] 'twenty'.

- Zero (or glottal stop) onset is indicated by အ. However, with loanwords, there is also a small set of separate symbols for zero onset plus certain vowel+tone. (However, unlike most Indic scripts, these 'independent vowel symbols' do not cover the entire range of vowels.) They are collated together with the regular forms with အ plus vowel. The following are the independent vowel symbols, preceded by the normal rendition formed with အ plus vowel:

- အိ / ဣ i.

- အီ / ဤ i

- အု / ဥ u.

- အူ / ဦ u

- အူး / ဦး u:

- အေ / ဧ e

- အေး / ဧး e:

- အော / ဩ au:

- အော် / ဪ au

- *: When ံ is not accompanied by a vowel symbol, it signifies am, and is usually placed between အော် / ဪ au and အို ui, as shown by the position of the * in the table towards the bottom of the first column. If there is a vowel symbol ိ i or ု u, ိံ im or ုံ um is collated together with ိမ် im or ှမ် um respectively

- In the phonology of modern standard Burmese, there are only two phonological codas left: all obstruent codas are merged into a glottal stop /-ʔ/, and the nasal codas are merged into a placeless /-N/. With /-N/, the phonetic realisation is that the vowel is nasalised, and it may be followed by a nasal consonant at the same place of articulation as the following consonant

- Apparently with loanwords, လ l ရ r~j ဝ w သ s can function as orthographical codas (with ် a.sat, or the top of a pair of stacked consonant), but they are silent, and the vowel in front of it functions as if it is in an open syllable (?) (this says so). In earlier times, အို ui was spelt အိုဝ်.

- The symbol င်္ is the functionally same as the preceding symbol followed by the coda symbol င် -ng.

- With the coda symbol ည် -ny, the nasal is lost. The vowel is usually [ɛ] in colloquial register, and [i] in literary register. In a few cases the vowel is [e]

- Tone marks:

- No tone mark

- syllable has no coda symbol: low tone (low tone is 'no dot' in transctiption), except အ a. အိ i. အု u. in creaky tone (these correspond with short vowel symbols in other Brahmic scripts), and အဲ ai: [ɛ] အို au: [ɔ] in high tone.

- syllable has nasal coda symbol: low tone

- syllable has obstruent coda symbol: no tonal contrast

- ့ creaky tone (creaky tone is 'one dot' . in transcription)

- း high tone (high tone is 'two dots'/colon : in transctiption)

- No tone mark

In addition, in cases with the consonant diacritic ွ -w-:

| အွတ် wat | အွပ် wap | ||

| [waʔ] / [ʔʊʔ] | [waʔ] / [ʔʊʔ] | ||

| အွန် wan | အွမ် wam | ||

| [wàN] / [ʔʊ̀N] | [wàN] / [ʔʊ̀N] | ||

| အွန့် wan. | အွမ့် wam. | ||

| [wa̰N] / [ʔʊ̰N] | [wa̰N] / [ʔʊ̰N] | ||

| အွန်း wan: | အွမ်း wam: | ||

| [wáN] / [ʔʊ́N] | [wáN] / [ʔʊ́N] |

In Upper Burma/Mandaley, the pronunciation is [waʔ] / [waN], while in Lower Burma/Yangon, the pronunciation is [ʊʔ] / [ʊN], and apparently this has merged into [ɪʔ] / [ɪN] for some people middle aged and younger. Both the Upper and Lower Burmese pronunciations of these are considered standard.

Rimes organised phonologically

The following are the rimes orgnised phonologically. The onset symbol used is the zero/glottal stop onset အ, or ဝ w when followed by the long form ါ a. Also read the section above for further explanations (e.g. how syllables can be reduced).

| creaky tone . | low tone | high tone : | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [a] | အ a. | အာ / ဝါ a | အား / ဝါး a: | |

| [i] | အိ (ဣ) i. / အည့် any. | အီ (ဤ) i / အည် any | အီး i: / အည်း any: | |

| [u] | အု (ဥ) u. | အူ (ဦ) u | အူး (ဦး) u: | |

| [e] | အေ့ e. (/ အည့် any.) | အေ (ဧ) e (/ အည် any) | အေး (ဧး) e: (/ အည်း any:) | |

| [ɛ] | အဲ့ ai. / အည့် any. | အယ် ai / အည် any | အဲ ai: / အည်း any: | |

| [o] | အို့ ui. | အို ui | အိုး ui: | |

| [ɔ] | အော့ / ဝေါ့ au. | အော် / ဝေါ် (ဪ) au | အော / ဝေါ (ဩ) au: | |

| [aʔ]/[aN] | အတ် at / အပ် ap | အန့် an. / အမ့် am. / အံ့ am. | အန် an / အမ် am / အံ am | အန်း an: / အမ်း am: / အံး am: |

| [ɪʔ]/[ɪN] | အစ် ac | အင့် ang. / အဉ့် any. | အင် ang / အဉ် any | အင်း ang: / အဉ်း any: |

| [ʊʔ]/[ʊN] | အွတ် wat / အွပ် wap | အွန့် wan. / အွမ့် wam. | အွန် wan / အွမ် wam | အွန်း wan: / အွမ်း wam: |

| [ɛʔ] | အက် ak | |||

| [aɪʔ]/[aɪN] | အိုက် uik | အိုင့် uing. | အိုင် uing | အိုင်း uing: |

| [aʊʔ]/[aʊN] | အောက် / ဝေါက် auk | အောင့် / ဝေါင့် aung. | အောင် / ဝေါင် aung | အောင်း / ဝေါင်း aung: |

| [eɪʔ]/[eɪN] | အိတ် it / အိပ် ip | အိန့် in. / အိမ့် im. / အိံ့ im. | အိန် in / အိမ် im/ အိံ im | အိန်း in: / အိမ်း im: / အိံး im: |

| [oʊʔ]/[oʊN] | အုတ် ut / အုပ် up | အုန့် un. / အုမ့် um. / အုံ့ um. | အုန် un / အုမ် um / အုံ um | အုန်း un: / အုမ်း um: / အုံး um: |

Georgian

I read through this:

- Harris, Alice C. 1981. Georgian syntax: a study in relational grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

I read parts of these:

- Hewitt, B. George. 1995. Georgian: a structural reference grammar. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Hewitt, B. George. 2005. Georgian: a learner's grammar. 2nd edition. London/New York: Routledge.

Flagging and indexing of core gramamtical relations

In Georgian, the inventories of case and personal affixes that can be used to mark core grammatical relations is small. Nonetheless, the same markers are used in different ways, based on the verb class, and also the tense-aspect-mood of the verb for some verb classes. With these complex patterns, and some other morphosyntactic behaviours, different linguistics have been defining/arguing for different mappings between the arguments and the grammatical relations based on different morphosyntactic criteria.

Verb classes. The verbs are commonly divided into four classes. (Some linguists make finer distinctions.) I will simply call them Classes I, II, III, and IV. Prototypically:

- Class I verbs are fully transitive. Causatives are in class I.

- Class II verbs are intransitive (i.e. no direct objects; some can have indirect objects). Some are intransitive counterparts of class I verbs, e.g. class I ვ-წონ-ი v-ts'on-i 'I weigh someone/something' vs. the static class II ვ-წონ-ებ-ი v-ts'on-eb-i 'I weight (e.g., X kg)'. Passives are in class II. The copula ყოფნა q'opna is also in class II. Most class II verbs have subjects that are not agentive. Nonetheless, (all?) active motion verbs are also class II verbs, e.g. მო-ვ-დი-ვარ mo-v-di-var 'I come'. Class III verbs tend to have voluntary subjects. Many class III verbs can be either intransitive of transitive, e.g. ვ-თამაშ-ობ v-tamaš-ob 'I play', ვთამაშობ ბურთს vtamašob burts 'I play ball'. However, within this class III are also meteorological verbs, and some intransitive verbs with non-voluntary subjects, e.g. ვ-წვალ-ობ v-ts'val-ob 'I suffer'.

- Class IV verbs have the Experiencer marked with Set II (the m- set) cross-referencing, which is usually used for object, e.g. მ-ი-ყვარ-ს m-i-q'var-s 'I love him/her', მ-ყავ-ს m-q'av-s 'I have him/her', მ-ცხელ-ა m-tsxel-a 'I am/feel hot'.

There are many cases within each class that deviates from these transitivity prototypes. These verb classes are also characterised by other verbal morphologies, most of which are not discussed here.

Tense-aspect-mood. Each paradigm of tense-aspect-mood is traditionally called in English 'screeve' (from მწკრივი mts'k'rivi 'row'). The screeves can be divided into three series (the labels of the individual screeves often differ slightly in different discriptions:

- Series I, future and present: future, conditional, future subjunctive; present, imperfect, present subjuctive

- Series II, aorist: aorist, optative

- Series III, perfect: perfect, pluperfect, perfect subjunctive (The 'perfect' is most usually a non-visual evidential.)

Core cases. There are three core cases, they are usually called 'nominative', 'ergative', and 'dative'. Their forms vary depending on whether the noun/adjective stem they are attached to ends in a consonant or a vowel.

- noun, C-: NOM -i, ERG -ma, DAT -s

- noun, V-: NOM -∅, ERG -m, DAT -s

- adjective, C-: NOM -i, ERG -ma, DAT -∅

- adjective, V-: -∅ (vowel-ending adjectives are invariant in general)

There are some class IV verbs of which the stimulus (the "object") is marked with a genitive case (noun: -is/-s, stems ending in -a or -e usually have -a/-e deleted and take -is; adjective: -i/-∅), instead of the usual nominative case. However, one line of thought is that since these genitive-marked nominals are not marked with a core case, nor cross-referenced, these nominals are oblique. These cases are not discussed further here.

There are three case marking patterns (-თვის -tvis below is a postposition that governs the genitive case):

| Case pattern ↓ | subject | direct object | indirect object |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | ERG | NOM | DAT |

| B | NOM | DAT | DAT |

| C | DAT | NOM | GEN-tvis |

These three case marking patterns are used with the following verb classes/screeves:

| Verb ↓ | Case ↘ | TAM → | Series I | Series II | Series III |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | B | A | C |

| Class II | B | B | B |

| Class III | B | A | C |

| Class IV | C | C | C |

With case pattern C, there is also Harris (1981)'s opinion that pattern C is a derivative of pattern B, and in pattern C, the DAT-marked nominal is the indirect object, the NOM-marked nominal the subject, and the tvis nominal an oblique object. The derivation from the normal pattern B is as follow: i) the original subject underwent 'inversion', i.e. demotion to indirect object, and hence marked with DAT; ii) the original indirect object becomes an oblique, marked with -tvis; and iii) since there is now no subject, 'unaccusativity' is activated, i.e. the original direct object is promoted to subject, and hence this nominal is marked with NOM. Please see Harris (1981) for her arguments and exact wording. One fact that makes this account for pattern C attractive is that the case marking aligns with the cross-referencing: i) the NOM-marked nominal, traditionally regarded as the direct object, is now regarded as the subject, and it aligns with set I cross-referencing on the verb, which is usually used for subjects; ii) the DAT-marked nominal, traditionally regarded as the subject, is now regarded as the indirect object, and it aligns with the set II cross-referencing, which is usually used for objects; iii) the tvis-marked nominal, traditionally regarded as the indirect object, is now regarded as an oblique, and this correctly matches the fact that this tvis-marked nominal is not cross-referenced. This set of operations occur in TAM series III for verb classes I and III, and in verb class IV. (She also had to formulate that these do not occur twice for class IV verbs in series III.)

Nonetheless, the world is not perfect, and there is one trait that suggests that synchronically, in some ways speakers view the DAT-marked nominal in pattern C as the subject: for third person references, plural subject references can be cross-rerenced by a plural suffix, whereas objects are never cross-referenced as plural; in pattern C, when both arguments are third person, it is the DAT-nominal that can have its plurality cross-referenced by a plural suffix -თ -t, while the NOM-nominal cannot.

Harris' account of the DAT/NOM/-tvis nominal in pattern C being IO/SUB/oblique is at least diachronically correct, while the traditional account of the DAT/NOM/-tvis nominal being SUB/DO/IO is also not without reason. Here I will simply acknowledge that things don't line up nicely, and, when dealing with pattern C, simply call them the DAT-relation/NOM-relation/tvis-relation. (While for patterns A and B, I'll use the terms SUB/DO/IO as usual.)

Cross-referencing. There are two sets of verbal cross-referencing affixes in Georgian (an agreeing nominal does not need to occur): Set I and Set II. Set I is used for subjects. Set II is used for objects, with separate affixes for direct and indirect objects for third person. For case pattern C, Set I is used for the NOM-relation, and set II (indirect object) is used for the DAT-relation. In some verb forms, an auxiliary verb is used in place of a normal set I affix; this auxiliary verb is laregly identical in form as the copula, which itself contains set I affixes. An example is მ-ი-ყვარ-ხარ m-i-q'var-xar 'I love you', where 'I' is cross-referenced with a set II m-, and 'you' is cross-referenced by the auxiliary -xar, identical in form to the copular ხარ xar 'you (sg) are'.

| Set I | singular | plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | ვ- | ვ-[...]-თ |

| v- | v-[...]-t | |

| 2nd person | ∅(/ხ-) | ∅(/ხ-)[...]-თ |

| ∅(/x-) | ∅(/x-)[...]-t | |

| 3rd person | -ს/-ა/-ო | -ან/-ენ/-ნენ/-ეს |

| -s/-a/-o | -an/-en/-nen/-es |

| Auxiliary (Set I) | singular | plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | (ვ-)[...]-ვარ | (ვ-)[...]-ვართ |

| (v-)[...]-var | (v-)[...]-vart | |

| 2nd person | -ხარ | -ხართ |

| -xar | -xart | |

| 3rd person | -ა/-ს | -ა/-ს |

| -a/-s | -a/-s |

The third person allomorphs are morphologically conditioned; it depends on the verb class and screeve. The second person ხ- x- is rare: a) in the present indicative copulas ხარ xar 'you(sg) are' and ხართ xart 'you(pl) are'; b) in the motion verb in the future and aorist series (-თ -t in the following indicates plural subjects): future მო-ხ-ვალ-(თ) mo-x-val(-t) 'you will come', conditional მო-ხ-ვიდ-ოდ-ი(-თ) mo-x-vid-od-i(-t), future subjunctive მო-ხ-ვიდ-ოდ-ე(-თ) mo-x-vid-od-e(-t); aorist მო-ხ-ვედ-ი(-თ) mo-x-ved-i(-t) 'you came', aorist subjunctive (optative) მო-ხ-ვიდ-ე(-თ) mo-x-vid-e(-t). (The preverb მო- mo- can be substituted by other preverbs, e.g. მო-ხ-ვალ mi-x-val 'you will go'.)

| Set II | singular | plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | მ- | გვ- |

| m- | gv- | |

| 2nd person | გ- | გ-[...]-თ |

| g- | g-[...]-t | |

| 3rd person direct object | ∅- | ∅- |

| ∅- | ∅- | |

| 3rd person indirect object | ∅-/ს-/ჰ- | ∅-/ს-/ჰ-[...](-თ) |

| ∅-/s-/h- | ∅-/s-/h-[...](-t) |

As for the set II third person indirect object affixes: a) ს- s- in front of ც- წ- ძ- ჩ- ჭ- ჯ- თ- ტ- დ- | ts- ts'- dz- tš- tš'- dž- t- t'- d- (all the coronal plosives and affricates); b) ჰ- h- in front of ქ- კ- გ- ყ- | k- k'- g- q'- (all the dorsal plosives) or პ- p'-; and c) ∅ elsewhere. (One line of thinking is that) third person objects never take the plural suffix -თ -t; nonetheless, in case marking pattern C, the DAT-relation is now viewed as the subject, and the corresponding set II third person affix can take the plural suffix -თ -t if the NOM-relation is also third person.

A verb must have a set I affix. If the relation cross-referenced by a set II affix is empty, it is cross-referenced as 3SG direct object, i.e. ∅, by default. These prefixes and suffixes occur at the outer-most periphery of the verb, with the exception that preverbs can exist in front of a cross-reference prefix.

Combining cross-referencing affixes. There is a constraint that at most one non-zero prefix and one non-zero suffix can occur (the internal structure of the copula-like auxiliaries does not count). When more than one is logically needed in the prefix or suffix slot, there is a hierarchy as to which one is kept and which one is deleted (in the list below, > signifies 'has precedence over'):

- Prefixes: Set II 2SG გ- g- > Set I 1SG ვ- v- (e.g.

ვ-გ-მალ-ავv-g-mal-av 'I hide you(sg)') - Prefixes: Set I 1SG ვ- v- > Set II 3SG (IO) ს-/ჰ- s-/h- (e.g. მი-ვ-

ს-წერ mi-v-s-c'er 'I shall write to him/her/them' (cf. მი-∅-ს-წერ mi-∅-s-c'er 'you will write to him/her/them)) - Suffixes: Set I 3PL -ან/-ენ/-ნენ/-ეს -an/-en/-nen/-es > PL -თ -t > Set I 3SG -ს/-ა/-ო -s/-a/-o (e.g. გ-მალ-ავ-ენ

-თg-mal-av-en-t'they hide you(pl)', გ-მალ-ავ-ს-თ g-mal-av-s-t 's/he hides you(pl)') - Suffixes: two plural suffixes -თ -t becomes one (e.g.

ვ-გ-მალ-ავ-თ-თv-g-mal-av-t-t'we hide you(pl.)')

For prefixes, see below for what happens when there is a 2SG direct object and 3SG indirect object. For the suffixes, it can be reworded like this: any plural suffix has precedence over the plural suffix -თ -t or a singular suffix.

These deletion rules can create two homonym sets, e.g. გმალავთ gmalavt 'we hide you(sg)', 'I hide you(pl)', 's/he hides you(pl)', or 'we hid you(pl)'; გმალავენ gmalaven 'they hide you(sg)' or 'they hide you(pl)'. In the table below, მალ mal is the verb root 'hide', and -ავ -av is a 'thematic suffix' (which is used primarily in the present/future series; in this case the verbs are in present indicative). Set I indexes the subject, and Set II the object, so, for instance, Set I 2SG and Set II 1sg მმალავ mmalav means 'You(sg) hide me'.

| Set I → | Set II ↓ | 1SG | 2SG | 3SG | 1PL | 2PL | 3PL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1sg | მ-მალ-ავ | მ-მალ-ავ-ს | მ-მალ-ავ-თ | მ-მალ-ავ-ენ | ||

| m-mal-av | m-mal-av-s | m-mal-av-t | m-mal-av-en | |||

| 1pl | გვ-მალ-ავ | გვ-მალ-ავ-ს | გვ-მალ-ავ-თ | გვ-მალ-ავ-ენ | ||

| gv-mal-av | gv-mal-av-s | gv-mal-av-t | gv-mal-av-en | |||

| 2sg | გ-მალ-ავ-ს | გ-მალ-ავ-ენ | ||||

| g-mal-av-s | g-mal-av-en | |||||

| 2pl | გ-მალ-ავ |

გ-მალ-ავ-ენ |

||||

| g-mal-av |

g-mal-av-en |

|||||

| 3 | ვ-მალ-ავ | მალ-ავ | მალ-ავ-ს | ვ-მალ-ავ-თ | მალ-ავ-თ | მალ-ავ-ენ |

| v-mal-av | mal-av | mal-av-s | v-mal-av-t | mal-av-t | mal-av-en |

Two more comments need to be made. Reflexivation is indicated by the noun თავი tavi 'head', sometimes preceded by a possessive pronoun, e.g. ჩემი თავი tšemi tavi 'myself' (3SG reflexive is თავისი თავი tavisi tavi). This reflexive nominal is cross-referenced as third person (and hence the combinations of first person–first person and second person–second person do not feature in the table above). For instance, ჩემს თავს ვ-ა-ქ-ებ tšem-s tav-s v-a-k-eb (my-DAT head-DAT 1SG-NV-praise-TS) 'I praise myself'. Often, subjective version is used (ი- i- in the following example), in which case the possessive phrase is not used, e.g. თავს მო-ვ-ი-კლ-ავ tav-s mo-v-i-k'l-av (head-DAT PV-1-SV-kill-TS) 'I shall kill myself'.

We have seen above that there cannot be more than one non-zero cross-reference prefix. When there are a first or second person direct object and an indirect object, a more drastic approach is used than simply deleting one of the object prefixes: the direct object nominal is changed to თავი tavi 'head' preceded by a first or second person possessive adjective, and it is cross-referenced on the verb as third person, i.e. zero. For instance, შენ-ს თავ-ს მ-ა-ძლ-ევ-ენ šen-s tav-s m-a-dzl-ev-en (your-DAT head-DAT 1SG-NV-give-TS-3PL 'they give you(r head) to me'.

Chinese Calendar

The following is a relatively non-technical description of the Traditional Chinese Calendar. This is compiled from information gathered from various webpages, especially English and Chinese Wikipedia pages.

Nowadays, the Western Gregorian Calendar is used by default in the various Chinese societies. However, the dates of traditional festivals like Chinese New Year and Mid-Autumn Festival are still calculated using the Traditional Chinese Calendar. The rules of the Chinese Calendar have changed over the centuries; this article is only talking about how the Chinese Calendar is calculated nowadays.

In this article, Traditional Chinese Characters are followed by Cantonese Jyutping before slash, and Mandarin Pinyin after slash.

Day and Month

Traditionally, a day is divided into twelve time sections. One Chinese time section lasts for two Western hours. Nowadays, the Western convention of dividing a day into twenty-four hours is followed in Chinese societies. Chinese astronomists have always considered midnight as the beginning of a day. However, for many Chinese astrologists, the beginning of the day is the beginning of the rat time section (子時 zi2 si4 / zǐ shí), which starts one Western hour before midnight. The rat time section lasts from 23:00 till the end of 00:59. For many Chinese astrologists, the rat time section is the first time section of the day. For Chinese astronomists, the rat time section is then a time section which straddles two days. Due to this difference in the interpretation of when a day starts, some people begin their ceremonies/celebrations for, e.g., new years at midnight, while other people begin theirs one Western hour before midnight.

Significant dates for the calculation of the Chinese calendar, e.g. the first day of the month, are calculated based on particular lunar or solar moments occuring during those dates, and the dates are demarcated by 00:00 in UTC+8, the time zone currently used by PRC and ROC.

The month is based on the lunar cycle. The first day of a month is the day that contains the moment of new moon. (New moon is when the moon is least visible; the moon is at the same ecliptic longitude, or "sky longitude", as the sun.) The time between two new moons varies between 29.18 and 29.93 days (due to the orbit/gravity differences between the moon, earth, and sun). Each month in the Chinese Calendar is 29 or 30 days long.

The first ten dates in a month in the Chinese calendar are called 初一 (co1 jat1 / chū yī [first one]), 初二 (co1 ji6 / chū èr [first two])... till 初十 (co1 sap6 / chū shí [first ten]). The rest of the dates in a month are normal numerals: 十一 (sap6 jat1 / shí yī [ten one]) 'eleven', 十二 (sap6 ji6 / shí èr [ten two]) 'twelve', 十三 (sap6 saam1 / shí sān [ten three]) 'thirteen'... 十九 (sap6 gau2 / shí jiǔ [ten nine]) 'nineteen', 二十 (ji6 sap6 / èr shí [two ten]) 'twenty', 二十一 (ji6 sap6 jat1 / èr shí yī [two ten one]) 'twenty-one'... till 二十九 (ji6 sap6 gau2 / èr shí jiǔ [two ten nine]) 'twenty-nine' or 三十 (saam1 sap6 / sān shí [three ten]) 'thirty'. In Cantonese (and many other Sinitic languages), the first two syllables in 二十一 (ji6 sap6 jat1 [two ten one]) 'twenty-one' to 二十九 (ji6 sap6 gau2 [two ten nine]) 'twenty-nine' are often contracted to 廿 (Cantonese jaa6), e.g. 廿一 (jaa6 jat1 [twenty one]), 廿四 (jaa6 sei3 [twenty four]).

Other than the normal date names, there are twenty four special date names in a year. These are the solar terms (節氣 zit3 hei3 / jié qì), corresponding with each 15° along the ecliptic (position of the earth in relation to the sun), starting fron the Spring Equinox. Every second solar term is a zodiac point (中氣 zung1 hei3 / zhōng qì; every 30° from the Spring Equinox). Zodiac points are used for the calculation of leap months (see below).

The First Month of a year is called 正月 (zing1 jyut6 / zhēng yuè; notice that 正 in 正月 is not pronounced zing3 / zhèng). The Second to Twelfth Months are simply called 二月 (ji6 jyut6 / èr yuè [two month]), 三月 (saam1 jyut6 / sān yuè [three month]) etc. until 十一月 (sap6 jat1 jyut6 / shí yī yuè [ten one month]) and 十二月 (sap6 ji6 jyut6 / shí èr yuè [ten two month]). The last two months are also called 冬月 (dung1 jyut6 / dōng yuè [winter month]) and 臘月 (laap6 jyut6 / là yuè [meat_cure month]) respectively. In English I call them 'First Month', 'Second Month' etc. till 'Eleventh Month' and 'Twelfth Month'. A leap month (see below) is called 閏[N]月 (jeon6 [N] jyut6 / rùn [N] yuè [leap [N] month]), with [N] being the number/name of the preceding month, e.g. 閏七月 (jeon6 cat1 jyut6 / rùn qī yuè [leap seven month]) 'Leap Seventh Month' comes after 七月 (cat1 jyut6 / qī yuè [seven month]) 'Seventh Month', and before 八月 (baat3 jyut6 / bā yuè [eight month]) 'Eighth Month'.

(Some people say that 臘月 (laap6 jyut6 / là yuè [meat_cure month]) refers specifically to the last month of the year. In case of an (extraordinarily rare) Leap Twelfth Month (see below), the regular Twelfth Month should be called 十二月 (sap6 ji6 jyut6 / shí èr yuè [ten two month]), while the Leap Twelfth Month should be called 臘月 (laap6 jyut6 / là yuè [meat_cure month]) or 閏十二月 (jeon6 sap6 ji6 jyut6 / rùn shí èr yuè [leap ten two month]). *閏臘月 (jeon6 laap6 jyut6 / rùn là yuè [leap meat_cure month]) is hence an anomaly.)

Leap Month and Year

Twelve lunar months add up to about 354.47 days. On the other hand, one solar year is about 365.24 days. Leap months are added to the Chinese calendar from time to time to make the years catch up with the solar cycle. In other words, a leap month is added in certain years so that the months are roughly in sync with the seasons. In normal circumstances, the correspondence between Western and Chinese Calendar dates repeates every 19 years (Metonic cycle; moon phases repeats every 19 solar years). For instance, a person's birthday according to the Western and Chinese calendars most usually fall on the same day on their 19th, 38th, 57th etc. birthday. Within each 19-Chinese-year cycle are 7 leap months, with each year having at most one leap month (i.e. each year can have 12 or 13 months). In each decade, there are 3 or 4 years with a leap month. Years with a leap month are 2 to 3 years apart. A normal Chinese year has around 354 days, while a Chinese year with a leap month has around 384 days.

A solar year is dissected by 12 zodiac points (中氣 zung1 hei3 / zhōng qì). Starting from the March Equinox (Northern Spring Equinox; i.e. the point when the sun is right above the equator, and gradually moving north towards the Tropics of Cancer), each 30˚ on the ecliptic (the earth moves 30° in relation to the sun) is a zodiac point. The Chinese zodiac points fall sometime between the 18th and 24th (inclusive) of each Western month. Already familiar to most Western readers are the two equinoxes and the two solstices. The twelve zodiac points make a full 360°. The 12 zodiac points are (the actual dates can be ± 1 day from the ones listed below):

- 000° 春分 ceon1 fan1 / chūn fēn 'Spring Equinox' March 21

- 030° 穀雨 guk1 jyu5 / gǔ yǔ 'Grain Rain' April 20

- 060° 小滿 siu2 mun5 / xiǎo mǎn 'Grain Buds' May 21

- 090° 夏至 haa6 zi3 / xià zhì 'Summer Solstice' June 21

- 120° 大暑 daai6 syu2 / dà shǔ 'Major Heat' July 23

- 150° 處暑 cyu5 syu2 / chǔ shǔ 'End Heat' Aug 23

- 180° 秋分 cau1 fan1 / qiū fēn 'Autumn Equinox' September 23

- 210° 霜降 soeng1 gong3 / shuāng jiàng 'Frost Descent' October 23

- 240° 小雪 siu2 syut3 / xiǎo xuě 'Minor Snow' November 22

- 270° 冬至 dung1 zi3 / dōng zhì 'Winter Solstice' December 22

- 300° 大寒 daai6 hon4 / dà hán 'Major Cold' January 20

- 330° 雨水 jyu5 seoi2 / yǔ shuǐ 'Rain Water' February 19

The zodiac point dates are roughly the same every year according to the Western Calendar, as the Western Gregorian calendar is purely solar. On the other hand, the zodiac point dates are different every year according to the Chinese Calendar, because the zodiac points are based on the solar cycle, whereas the months are based on lunar cycles, and the solar and lunar cycles do not match. The one fixed rule is that the Eleventh Month is the month with Winter Solstice in it. In a normal 12-month year, usually each month has one zodiac point in it.

The earth's orbit is not a perfect circle. During the Northern Winter, the earth is relatively close to the sun, and the earth travels faster. Around the December Solstice, the number of days between zodiac points are 29 or 30 days. The opposite is true in the Summer. Around the June Solstice, the number of days between zodiac points are 31 or 32 days.

In the Chinese calendar, if there are twelve new moons between two (Northern) Winter Solstices, then there is no leap month in that period. If there are thirteen new moons, then there is one leap month in that period. The leap month is the first month after the Winter Solstice that contains no Chinese zodiac point. In other words, this lunar month, from the day that contains a new moon, to the day before the day that contains the following new moon, fits within a 30° bracket on the ecliptic between two zodiac points. (Very occationally, there are two months with no zodiac points between two Winter Solstices; only the first month is called the Leap [N] Month, with N being the number/name of the preceding month. The second month is simply called the [N+1] Month as usual.)

Take the leap month in 2023 as an example. Between Winter Solstice 2022 and Winter Solstice 2023, there are 13 new moons. A leap month is needed in between. One observes that in (Gregorian) 2023 (UTC+8):

- New moon: February 20 at 15:05 (= a new month starts on Feb 20)

- Zodiac point of Spring Equinox: March 21 at 05:15

- New moon: March 22 at 01:23 (= a new month starts on Mar 22)

- New moon: April 20 at 12:12 (= a new month starts on Apr 20)

- Zodiac point of Grain Rain: April 20 at 16:07

- New moon: May 19 at 23:53 (= a new month starts on May 19)

The Chinese month that corresponds to February 20 – March 21 is a normal month, containing the zodiac point of Spring Equinox. Two Chinese months later, the month that corresponds to April 20 – May 18 is also a normal month, containing the zodiac point of Grain Rain. However, the month in between, March 22 – April 19, contains no zodiac point. (This month has 29 days, and there are 30 days between Spring Equinox and Grain Rain.) This is the first month without a zodiac point after Winter Solstice 2022. This Chinese month is hence a leap month. This leap month is called the Leap Second (2nd) Month, as the preceding month is the Second Month (third full month after the Winter Solstice).

By designating a month without zodiac point as a leap month, the default alignments between the twelve zodiac points and the twelve normal months are usually maintained. The Eleventh Month is the month with Winter Solstice. (This alignment trumps other alignments when there is a conflict.) The preceding example shows the usual alignment of the Second Month with Spring Equinox and the Third Month with Grain Rain. Summer Solstice is usually in the Fifth Month, and Autumn Equinox is usually in the Eighth Month.

As mentioned above, because the time between zodiac points are longer in the Northern Summer, leap months usually occur during the Summer. (A month is 29 or 30 days long, and the zodiac points are 31 or 32 days apart during the Summer.) Leap months during the Northern Winter are extraordinarily rare. The next Leap Ninth Month will be in 2109, Leap Tenth Month in 2166, Leap Eleventh Month in 2033 (see below), Leap Twelfth Month in 3358, and Leap First Month in 2262.

Leap months with 29 days are more common. (30-day months are harder to fit between zodiac points.) In the 20th century, there were 25 leap months with 29 days, and 12 leap months with 30 days. The figures given above for the rare Winter leap months are for leap months with 29 days. For 30-day leap months, the next Leap Ninth Month will be in 2576, Leap Tenth Month in 5191, Leap Eleventh Month in 6402, Leap Twelfth month in 8425, and Leap First Month in 9982.

Traditionally, years are named using the [A][B]年 (nin4 / nián [year]) formula. [A] is the "heavenly stem": a set of ten monosyllabic names, in a fixed order. The ten heavenly stems correspond with the five elements of wood, fire, earth, metal, and water, and the yang and yin versions of each of these. [B] is the "earthly branch": a set of twelve monosyllabic names, in a fixed order. The twelve earthly branches correspond with the twelve animals of the Chinese zodiac signs. With each new year, [A] and [B] roll over to the next name in the set. This creates a 60-year cycle, after which the names are repeated in the same order. See this article on the Sexagenary cycle.

These days, most commonly used is the Western year numbering system, e.g. 2022 is 二零二二年 (ji6 ling4 ji6 ji6 nin4 / èr líng èr èr nián [two zero two two year]). In ROC, the era name 民國 (man4 gwok3 / mín guó [republic]) is also used, with 2022 being ROC Year 111 民國一百一十一年 (man4gwok3 jat1 baak3 jat1 sap6 jat1 nin4 / mínguó yī bǎi yī shí yī nián [republic one hundred one ten one year]). These are names of years according to the Western calendar. However, people may use these year numberings for the Traditional Chinese years as well, as these numberings are easier for people to comprehend than the traditional names, e.g. 壬寅年 (jam4 jan4 nin4 / rén yín nián) 'yang-water tiger year' for the Chinese year that began in Gregorian February 1 2022.

Chinese New Year

With the Eleventh Month being the month containing the (Northern) Winter Solstice, the Chinese New Year (First Day of the First Month) is thus the second new moon after the Winter Solstice. (Unless there is the extraordinarily rare Leap Eleventh or Leap Twelfth Month, then the New Year is the third new moon after the Winter Solstice.) In Western Calendar, the Chinese New Year occurs between January 21 and February 20. (This corresponds roughly to Aquarius in Western astrology, which is approximately January 20 to February 18.)

PRC and ROC calculate the moon and sun positions based on UTC+8 / 120°E. On the other hand, Vietnam makes its calculations based on UTC+7 / 105°E. Occationally the Vietnamese New Year is one day earlier than the Chinese New Year, because the moment of new moon is 23:xx in Vietnamese time zone, and 00:xx the following day in Chinese time zone. A similar phenomenon occurs in Korea and the Ryukyus, as they make their calculations based on UTC+9 / 135°E. Hence the Korean and Ryukyuan New Years are sometimes one day later than the Chinese New Year.

Tibetans and Mongols have a similar lunisolar calendar as the Chinese Calendar. There is sometimes a one-day difference between the Tibetan/Mongol New Year and the Chinese New Year. Sometimes there is a one-month difference, due to the differences in how the leap month is calculated.

The Year 2033 bug

(Wikipedia pages in Chinese, Japanese, Korean.)

In the past, some subtle differences between the current and superseded versions of the calendar rules were not widely understood. People were applying different versions of the rules, causing differing opinions on when the leap month in 2033 will occur. Among other problems, this affects the electronic conversion between Western and Chinese dates. This problem has largely been resolved in software built since the 1990s, but in all likelihood there will be a very small number of rogue software causing trouble in 2033.

The second half of Chinese Year 2033 is a highly abnormal period when the new moons and the zodiac points often occur on the same dates. This has caused there to be three (!) months without zodiac points in the seven months after the Seventh Month 2033 and before the Second Month 2034. These three months are all potential leap months: A) the month after the Seventh Month 2033; B) the fourth month after that; and C) the second month after that (i.e. the month before the Second Month 2034). It is now clear to most people that it is month B that should be the leap month, as it is the first such month after Winter Solstice 2033 (and there are 13 new moons between Winter Solstice 2033 and Winter Solstice 2034). Month B is called the Leap Eleventh Month of 2033. The other months are "fake leap months", i.e. months that lack a zodiac point, but are not called a leap month. Month A in 2033 is disqualified as there are only twelve new moons between Winter Solstice 2032 and Winter Solstice 2033, and no leap month can occur during this period. Month A is called the Eighth Month of 2033. Month C in 2034 is disqualified, because there is already another month with no zodiac point (Month B) between it and the preceding Winter Solstice. Month C is called the First month of 2034.

Having two months with no zodiac points close to each other is very rare, let alone three. As discussed above, having such months in Winter is extraordinarily rare, and there are two of them during this Winter. The failure of the Eighth Month 2033 to become a leap month has caused the three zodiac points of Autumn Equinox, Frost Descent, and Minor Snow to fall in the Ninth, Tenth, and Eleventh Months instead of the Eighth, Ninth, and Tenth Months. The failure of the First Month 2034 to become a leap month has caused the zodiac point of Rain Water to fall in the Twelfth Month instead of the First Month. (The normal Eleventh and Twelfth Months then have two zodiac points each.) These are charted in this table.

In Japan, a total shift to the Western Gregorian calendar was made on (Western) New Year's day in 1873. Festivals are no longer observed according to the old lunisolar calendar. (Except the Ryukyus, which was not fully annexed by Japan until 1879. Some festivities there are still observed according to the old lunisolar calendar.) Despite having fallen into obscurity, the old Japanese lunisolar calendar is still kept track by some people. They are still using the pre-1873 Japanese rules for calculating the leap months. When there is a problem, there is no longer an authority to clarify or change the rules.

In the old Japanese rules, the Autumn Equinox must be in the Eighth Month. In 2033, there are three months separating the Fifth Month (Summer Solstice) and the Eighth Month (Autumn Equinox); there is only one month separating the Eighth Month (Autumn Equinox) and the Eleventh Month (Winter Solstice); and there are again three months separating the Eleventh Month 2033 (Winter Solstice) and the Second Month 2034 (Spring Equinox). People have different opinions on which month(s) should be the leap month(s), and what to do with the one month between the Eighth and the Eleventh month. (Cf. the current Chinese rules only fixate the Eleventh Month to the Winter Solstice, and are flexible with the other zodiac points.)

Zhuàng dialects

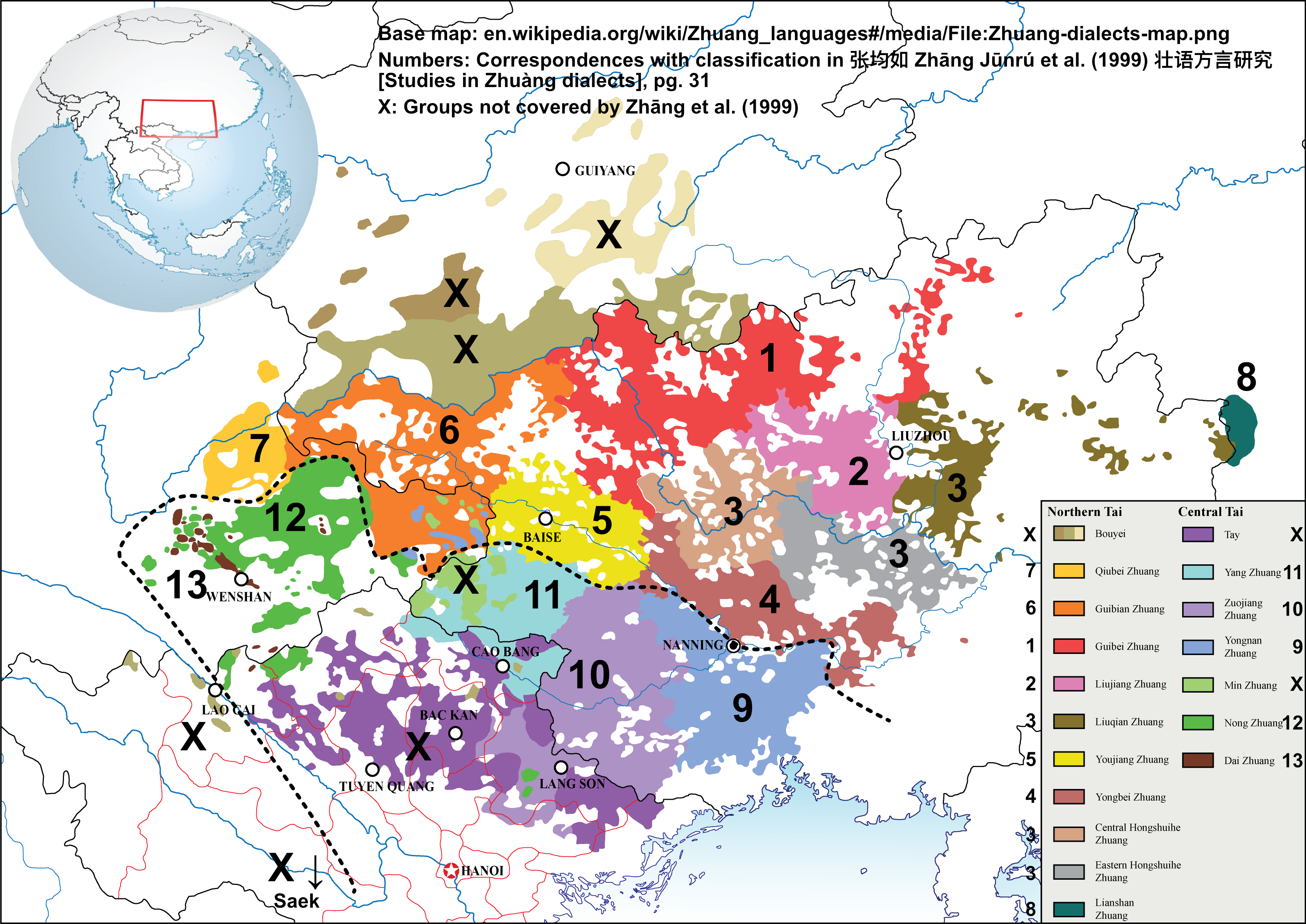

壮 [壯] Zhuàng is the term that China applies to the Northern Tai and Central Tai varieties in Guǎngxī, Guǎngdōng, and Yúnnán. The two groups are called "Northern dialects" and "Southern dialects" of Zhuàng respectively; from a Western linguistic point of view, these are at least two languages. To the north, the Northern Tai varieties in Guìzhōu are classified separately by China as Bouyei (布依 Bùyī). To the south, the Central Tai varieties in Vietnam are generally classified into two groups: a) Tày, which has been in Vietnam longer and more influenced by Vietnamese; and b) Nùng, which is basically extensions of the various Southern Zhuàng varieties in China (and they have been in Vietnam not as long). In addition, there are also Bouyei (Northern Tai) migrants in Vietnam, and they are classified separately as Bố Y.

The Tai language family is traditionally divided into Northern Tai, Central Tai, and Southwestern Tai. (Southwestern Tai includes the big languages like Thai and Lao.) The second map below shows the location of all Northern Tai and Central Tai varieties, except the Northern Tai language of Saek, spoken in Laos and Thailand much further south of the map. More-recent classifications of the Tai family include: a) Pittayaporn 2009, who has Northern Tai and parts of Yōngnán Zhuàng (Group 9; see below) as one branch, Central Tai as various branches, and Southwestern Tai as a low level branch within one of the Central Tai branches; b) Liao & Tai (2019), who divides Tai into "Northern Tai (Yay Proper)", which includes Northern Zhuàng (including Bouyei), Yōngnán Zhuàng, and Saek, versus "Southern Tai (Tai Proper)", which includes Central Tai and Southwestern Tai.

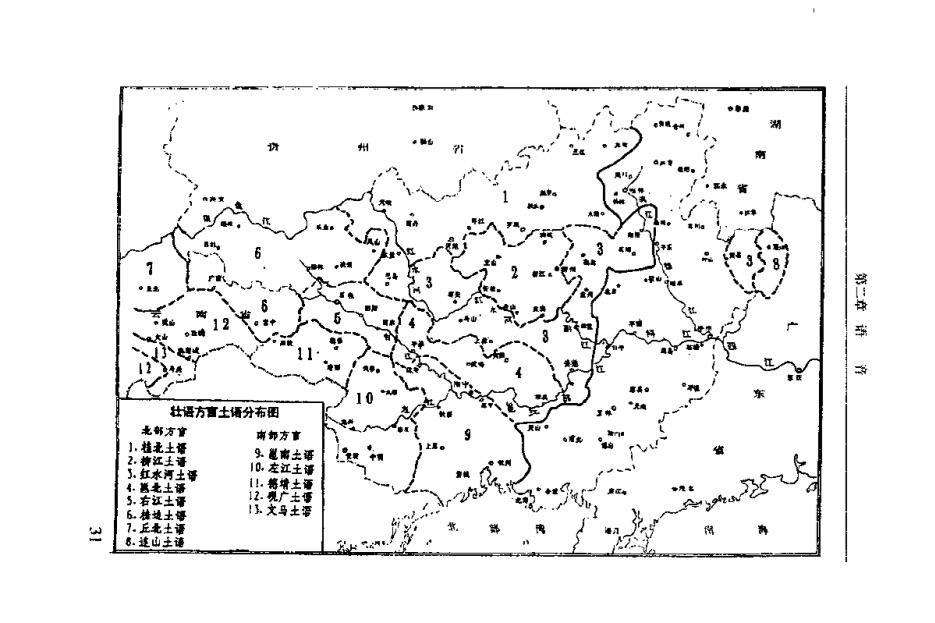

The first map below is from page 31 of Zhāng Jūnrú 张均如 et al. (1999) Zhuànyǔ fāngyán yánjiū 壮语方言研究 [Studies of Zhuàng dialects]. This shows their classification of the Zhuàng varieties into 13 dialect groups.

The following map has Mendduet's dialect map of Zhuàng–Bouyei–Nùng–Tày in Wikipedia as the base map. I added a dotted line (roughly) separating Northern Tai and Central Tai, and numbers corresponding to the numbering system in Zhāng et al. (1999)'s map (the map above). Group 3 Hóngshuǐhé 红水河 has been divided into three groups in the following map: Central Hóngshuǐhé, Eastern Hóngshuǐhé, and Liǔqián 柳黔. This follows Hanson & Castro (2010). Another group, Min Zhuang, is unnumbered in the following map because it is a newly discovered variety, and it has not been described in Zhāng et al. (1999). Varieties of Northern and Central Tai that are not classified as Zhuàng by China (varieties in Guìzhōu, Vietnam, and Saek) are also not studied by Zhāng et al. (1999), and hence also unnumbered in the following map.

One feature that separates Northern Tai and Central Tai is that Northern Tai lacks aspirated onsets, while Central Tai has both aspirated and non-aspirated plosives/affricates. (There is one exception: Group 8 Liánshān 连山 Zhuàng has developed aspirated plosives/affricates under strong Sinitic influence.) Newer reconstructions of Proto-Tai (e.g. Pittayaporn 2009) argue that Proto-Tai does not have aspirated onsets.

The following is a small summary of the main features of the 13 dialect groups of Zhuàng according to Zhāng et al. (1999: 32–50). Occationally I have also added some extra notes. There are two concepts that needs to be introduced here: a)"R sounds" refers to the reflexes of Proto-Tai *r- or *hr- which have not merged with the reflexes of other proto onsets; these modern reflexes include onsets like r- l- h- hl- ɬ- hj- j- z- ð-; b)"odd tones" refer to tones of syllables with voiceless or glottalised proto onsets, "even tones" refer to tones of syllables with voiced proto onsets.

- Guìběi 桂北

- autonym pu4 tsuːŋ6 (Zhuàng), pu4 baːn3 (village people), pu4 maːn2 (barbarian), pu4 ʔjai4 (Bouyei)

- has labialised onsets like pw- bw- mw- (in addition to common onsets like kw- ŋw- pj- mj- kj-)

- R sounds generally merged into j- in odd tones, and generally remain separate in even tones

- Liǔjiāng 柳江

- autonym pu4 tsuːŋ6, pu4 suːŋ6 (Zhuàng)

- has labialised onsets like pw- tw- dw- nw- ɲw- lw- tsw- θw- jw- hw- kjw- hjw-, and palatalised onsets like tj- dj- lj- tsj- θj- (in addition to common onsets like kw- ŋw- pj- mj- kj-)

- R sounds unmerged with other categories; in many places realised as hj-

- in closed syllables with a long high vowel, the vowel has an ə offglide (but not as prominent as in Yòujiāng and Yōngběi)

- has not broken i u into ei ou (unlike Hóngshuǐhé group)

- *aɯ is realised as ə, while *əɯ has merged into *ɯ (realised as ɯ)

- Hóngshuǐhé 红水河

- autonym pou4 tsuːŋ6 (Zhuàng), pou4 to3 (local people)

- ʔm- ʔn- ʔɲ- ʔŋ- have been retained; such syllables have odd tones (elsewhere they have usually merged with the non-glottalised nasals, while still being in odd tones)

- most places have an affricate ts-, corresponding with ɕ- θ- etc. elsewhere (many Zhuàng varieties lack affricates)

- in closed syllables with a long high vowel, the vowel has an ə offglide

- i u have broken into ei ou

- Yōngběi 邕北

- *pl- *ml- *kl- may be preserved as pl- ml- kl-, or they have become pj- mj- pj-, or p- t- k-

- in closed syllables with a long high vowel, the vowel has an ə offglide

- i u have often broken into ei ou

- Yòujiāng 右江

- autonym pu4 to3 (local people)

- R sounds have merged with l-

- *pl- *kl- (complex onsets of various sorts in other varieties e.g. pl- pɣ- pj-) are all tɕ- in Yòujiāng

- in closed syllables with a long high vowel, the vowel has an a offglide (the offglide is more open in quality than other dialects)

- as for syllables with a glottal or glottalised onset, when such syllables are pronounced in tone 3 in other dialects, in Yòujiāng these have tone 4

- Guìbiān 桂边

- autonym pu4 ʔjai4, pu4 ʔjoːi4 (Bouyei)

- relatively many labialised onsets e.g. lw- θw- tɕw- ɕw- jw- ʔjw-

- has contrasts /e/ /ɛ/ and /o/ /ɔ/

- R sounds generally merged into l-; some places (e.g. Lónglín 隆林) have kept R as ð-

- *kl- (often kl- kj- in other places) is tɕ- in Guìbiān; *k- in front of i e is also palatalised to tɕ-

- as for syllables with a glottal or glottalised onset, when such syllables are pronounced in tone 3 in other dialects, in Guìbiān these have tone 4 (same as Yòujiāng)

- Qiūběi 丘北

- autonym pu4 ʔi4, pu4 ʔjoːi4 (Bouyei), exonym Shā 沙

- pl-(pj-) ml-(mj-) kl-(kj-) elsewhere is p- m- k-(or tɕ-) in Qiūběi

- f- became w-, h- became ɣ-

- eː became ia or iə, o became ua or uə

- -k after a long vowel has been deleted

- as for syllables with a glottal or glottalised onset, when such syllables are pronounced in tone 3 in other dialects, in Qiūběi these have tone 4 (same as Yòujiāng and Guìbiān)

- *k- in front of i e is often palatalised to tɕ-

- Liánshān 连山

- autonym tshyːŋ6 θok8 壮族 (notice the Sinitic morpheme order)

- migrated from Group 2 Liǔjiāng area east to Guǎngdōng; language is relatively strongly Sinicised (in the area there are the Sinitic lects of Yuè (Cantonese and Gòulòu) and Northern Guǎngdōng Patois)

- developed aspirated plosive ph- th- tsh- kh- khj- khw-; these are unrelated to the aspirated plosives in Southern Zhuàng

- in some parts of Liánshān *ʔb- > p-, *ʔd- > l- (in other Zhuàng varieties, usually *ʔb- *ʔd- are kept, or merged with m-(~w-) n-)

- R sounds are all j-

- ɯ merged into u (e.g. -aɯ > -au)

- has front vowels œ y

- Yōngnán 邕南

- autonym pou4 tho3, hun2 tho3 (local people)

- there is often further tone splitting (beyond the basic voiceless / glotalised versus voiced onsets); e.g. in Yōngníng 邕宁 Xiàléng 下楞, tone 1 has been split further based on whether the proto onset is non-aspirated versus aspirated or glotalised

- in most areas, *ʔb- *ʔd- have merged into m- n-

- areas closer to Northern Zhuàng have often kept the R sounds separate; otherwise, in many areas, R sounds have merged with other onsets, in just odd tones or in both odd and even tones

- lexical forms are often closer to Northern Zhuàng than Southern Zhuàng varieties to the west

- Zuǒjiāng 左江

- autonym kɯn2 tho3 (local people)

- R sounds: in odd tones generally merged into h-, occationally th- kh- or khj-; in even tones generally merged into ɬ- l- n-

- in closed syllables with a long high vowel, in most places the vowel is not broken

- Déjìng 德靖 (Yang Zhuang)

- is said to be people who originally spoke a Kra language (cf. Yang in Buyang)

- autonym kən2 tho3 (local people)

- the glottality in ʔb- ʔd- has become less obvious; in some places these onsets have changed to m- n-

- simple *r- is generally kept as r- ~ ɹ-, ð-, or occationally l-

- *Cr- *Cl- are generally th- khj- (kj-) kh- h- in odd tones, l- n- ŋ- in even tones

- in Débǎo and Jìngxī, except for /a/ /a:/, the vowel length contrast is usually lost (the resulting vowels are usually phonetically long); in obstruent-ending syllables, what used to be long versus short vowels are still different in tones

- e begins with a slight i on-glide

- in Débǎo and Jìngxī, there are /e/ /ɛ/ and /o/ /ɔ/ contrasts

- Yànguǎng 砚广 (Nong Zhuang)

- autonym phu3 nɔŋ2, phu3 noːŋ2 (Nóng 侬). Mutually intelligibility is difficult with pu4 ʔjai4 / pu4 ʔjoːi4 ("Shā 沙", Group 7 Guìbiān Northern Zhuàng), and even harder with bu6 dai2 (Group 13 Wénmǎ), who lives amongst Nong people. Mutual intelligibility is better with Group 10 Zuǒjiāng and Group 11 Déjìng.

- kj- khj- in other Southern Zhuàng varieties are generally tɕ- tɕh- in Nong Zhuang

- *hr- is generally h- x-; *r- is generally r- l-

- there are tɕ- tɕh- ɕ- (Zhuàng varieties are normally poor with these distinctions)

- vowel length is lost in obstruent ending syllables, but their tones are still different

- Wénmǎ 文马 (Dai Zhuang)

- autonym bu6 dai2 (Dài 岱); they sometimes also use the exonym Tǔ 土 as autonym

- linguistically most aberrant amongst Zhuàng varieties, with some unusual retensions, and also many typological changes which are very rare for Zhuàng

- preserved Proto-Tai voiced plosives, affricates, and fricatives, except that b- d- have merged into ʔb- ʔd-

- complex onsets in other Zhuàng varieties have all been simplifed to p- ph- m- l- k- etc. in Dai Zhuang

- obstruent codas have all disappeared

- i u ə can be followed by -n or -ŋ, otherwise earlier nasal codas are only preserved as nasality in vowels

- animal sex morphemes are prefiexed and not suffixed